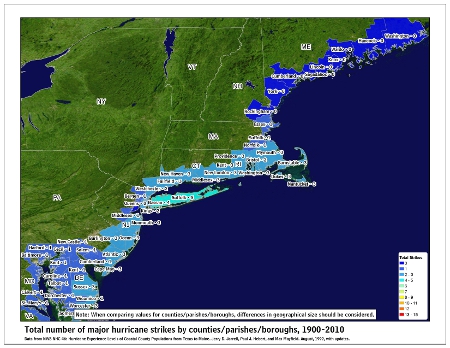

Tropical Storms Amanda (left) and Cristobal (right) near their peak intensities on May 31 and June 3 respectively | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| as Tropical Storm Amanda | |

| Formed | May 30, 2020 |

| Dissipated | May 31, 2020 |

| Tropical storm | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 40 mph (65 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 1003 mbar (hPa); 29.62 inHg |

| Meteorological history | |

| as Tropical Storm Cristobal | |

| Formed | June 1, 2020 |

| Extratropical | June 9, 2020 |

| Dissipated | June 12, 2020 |

| Tropical storm | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 60 mph (95 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 988 mbar (hPa); 29.18 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 46 total |

| Damage | ≥$865 million (2020 USD) |

| Areas affected | Central America (especially Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras), Mexico, Central United States, Great Lakes Region, Eastern Canada |

| IBTrACS: Amanda, Cristobal | |

Part of the 2020 Atlantic and Pacific hurricane seasons | |

Tropical Storm Amanda and Tropical Storm Cristobal were two related, consecutive tropical cyclones that affected Central America, southern Mexico, the Central United States, and Canada in late May and early June 2020. The first tropical cyclone formed in the East Pacific and was named Amanda. After crossing Central America, its remnants regenerated into a second one in the Gulf of Mexico and was named Cristobal. Amanda was the second tropical depression and the first named storm of the 2020 Pacific hurricane season, and Cristobal was the third named storm of the extremely active 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, and the earliest third named storm in the North Atlantic Ocean on record.[a] Cristobal's regeneration date in the North Atlantic eclipsed the date set by Tropical Storm Colin in 2016, which formed on June 5. It was also the first Atlantic tropical storm formed in the month of June since Cindy in 2017, and the first June tropical cyclone to make landfall in Mexico since Danielle in 2016.

Amanda developed out of a broad area of low pressure associated with a tropical wave, which moved off the coast of Nicaragua into the Pacific on May 29. The disturbance slowly developed a more well-defined circulation, and on May 30, the system was designated as Tropical Depression Two-E after finishing tropical cyclogenesis. Originally expected not to strengthen significantly, the storm nevertheless compacted and was upgraded to Tropical Storm Amanda at 09:00 UTC the next day. Three hours later, Amanda made landfall in southeast Guatemala. Once inland, Amanda rapidly weakened and degenerated into a remnant low over the region's rough terrain. However, the system's remnants survived, crossing Central America and Mexico.

On June 1, the system regenerated into Tropical Storm Cristobal over the Bay of Campeche. Cristobal then made landfall in the Mexican state of Campeche on the Yucatán Peninsula at 13:35 UTC on June 3, 2020, with 1-minute sustained winds of 60 mph (97 km/h),[b] causing torrential rainfall throughout the region. The storm slowly curved northward over Mexico and moved over the Gulf of Mexico, making a second landfall over southeastern Louisiana at 22:10 UTC on June 7. The system progressed north through the Mississippi Valley, managing to survive over land as a tropical depression, before finally becoming extratropical over southern Wisconsin at 03:00 UTC on June 10. Cristobal's extratropical remnant then moved north past Lake Superior and then over James Bay, before dissipating on June 12. The remnant moisture was subsequently absorbed into another system, which headed northeastward towards the Labrador Sea.

Tropical Storm Amanda produced torrential rainfall across Guatemala and severely impacted El Salvador, causing the worst natural disaster in the country since Hurricane Mitch in 1998; rivers overflowed and swept away buildings, damaging 900 homes and displacing over 1,200 people. Heavy rains also caused minor to moderate flooding in Mexico and Belize. Five people were killed in Honduras. Overall, Amanda resulted in an estimated $200 million in damage and killed 40 people in three countries.[2] Combined with Amanda, Cristobal led to nearly a week of devastating rainfall across Guatemala, El Salvador, and southern Mexico. Combined rainfall from Amanda and Cristobal totaled well over 15 inches (38 cm) of rain in some places, peaking at 26.48 inches (67.3 cm) in Jutiapa, Guatemala. Over 230,000 acres of crops were damaged in the Mexican state of Yucatán, leading to a damage estimate of US$184 million in Mexico. In the United States, Cristobal spawned multiple tornadoes and waterspouts along the Gulf Coast and the Midwest. Altogether, Cristobal caused at least US$665 million in damage and 6 fatalities. Throughout their entire lifespan, the cyclones killed 46 people and caused $865 million (2020 USD) in damages.[3]

Meteorological history

Amanda

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

On May 24, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) first discussed the possibility of tropical cyclogenesis in the East Pacific basin, due to a broad area of low pressure that was forecast to form off the coast of El Salvador with an associated tropical wave.[4] Furthermore, several other factors were favorable during the formation of Amanda, most notably a Kelvin wave traversing east over the far eastern portion of the basin and a mid-to-upper-level low forming off the coast of Mexico, both of which were enhanced large-scale convective activity.[4] A tropical wave moved off the west coast of Africa on May 18–19, and tracked generally westward across the Atlantic basin for several days, crossing over Panama and entering the Eastern Pacific basin on May 29.[4] As the tropical wave emerged into the Pacific, it caused the pre-existing disturbance that was being enhanced by a Central American Gyre (CAG) to become more organized.[4][5]

By May 30, the system attained a closed and defined low-level circulation and was considered sufficiently organized enough to be designated as Tropical Depression Two-E later that same day, remaining embedded within the eastern side of a Central American Gyre. The depression slowly intensified to a strength of 35 mph (56 km/h), with the aid of fairly-warm sea surface temperatures, and at the time, was considered unlikely to intensify further. The depression shifted northeastward than north-northeastward as it remained entrained into the larger gyre's circulation.[4] The system's satellite appearance improved, and the depression further strengthened to tropical storm strength and was named Amanda at 06:00 UTC on May 31.[4] Amanda improved further in organization up to landfall at 10:00 UTC that day, near Las Lisas, Guatemala.[4][6] Once inland, Amanda brought torrential rainfall to portions of Guatemala and El Salvador that produced flooding and landslides.[7] Amanda's appearance quickly deteriorated over land due to the mountainous landscape, and its low-level circulation center dissipated at 18:00 UTC on May 31.[4]

Cristobal

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

Amanda's remnant low survived the land interaction and continued to move north-northwestward for another day, steered by the CAG.[1][4][8][9][10][11] On June 1, as the system moved northward toward the Yucatán Peninsula, the NHC advised that in all likelihood, it would develop into an Atlantic tropical depression within the next few days.[6] At 21:00 UTC that same day, the system developed a new low-level circulation center and acquired enough convection to be designated as Tropical Depression Three in the North Atlantic basin, with maximum sustained winds of 30 mph (48 km/h).[12] For the next four days, the depression proceeded to make a slow counterclockwise loop over the region.[1] Located over the Bay of Campeche, the depression proceeded to slowly intensify throughout the rest of the day. On the morning of June 2, a U.S. Air Force Reserve hurricane hunter aircraft investigated the depression and found the system to be very close to tropical storm strength, and data from a subsequent midday flight indicated that wind speeds had increased to tropical storm-force, so the cyclone was given the name Cristobal. Because it had degenerated into a remnant low in the East Pacific basin before regenerating in the North Atlantic basin, the system was given a new name from the North Atlantic naming list, according to the NHC's policy on cross-basin storms.[a] This marked the earliest third named storm in the Atlantic, eclipsing the record set by Tropical Storm Colin in 2016, which formed on June 5.[13][14]

Cristobal strengthened as it stayed nearly stationary in the Bay of Campeche on the next day. The storm's development was reinforced by the moisture and the persistent onshore flow across parts of Central America, steered by a large counter-clockwise wind pattern known as the Central American Gyre.[15][16] Afterward the storm began slowly moving southward while gaining strength quickly, as it neared the Mexican coastline. Cristobal became more symmetrical, and its barometric pressure continued dropping. Later, at 13:35 UTC on June 3, reports from a Hurricane Hunter aircraft indicated that Cristobal had made landfall at peak intensity near Atasta, Mexico, just to the west of Ciudad del Carmen, with sustained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) and a central barometric pressure of 994 millibars (29.4 inHg).[17] Cristobal, beginning to lose its convective activity, began to slowly weaken as the day went on while it pushed further southeast into the Mexican state of Campeche.[1]

At 16:00 UTC on June 4, Cristobal was downgraded to tropical depression status,[15] with its satellite appearance continuously degrading. The depression lost most of its banding features due to prolonged interaction with land, and most of its convection was limited to the northeastern quadrant of the circulation. Then, while near the northwestern tip of Guatemala,[15] Cristobal made a cyclonic loop, as it was still embedded within the Central American Gyre, and the cyclone moved back across the Yucatán Peninsula before turning northward. During this time, the storm also started becoming better-organized on satellite imagery. At 09:00 UTC on June 5, Cristobal reintensified into a tropical storm, even though it was still situated over land.[1]

Cristobal exited the Yucatán on June 5 and entered the southern Gulf of Mexico. The much-broader cyclone moved further north as dry air and interaction with an upper-level trough to the east began to strip Cristobal of its central convection, with most of the convection being displaced to the east and north of the center, and thoroughly ridding Cristobal of a typical tropical cyclone structure. Reconnaissance aircraft found Cristobal slightly stronger on the afternoon of June 6, despite being poorly-organized. Observations from the NHC suggested that Cristobal resembled a subtropical cyclone rather than a tropical cyclone during this period, with the strongest winds and convection displaced well to the east of the center; however, the agency still classified Cristobal as a tropical storm. Tropical Storm Cristobal then made landfall on June 7 at 22:10 UTC, in southeast Louisiana, east of Grand Isle at its second peak intensity of 50 mph (80 km/h);[18] the barometric pressure at landfall was 992 millibars (29.3 inHg).[16]

After landfall, a blocking high-pressure area to the east caused Cristobal to turn to the northwest and slow down. The weakening storm moved directly over the New Orleans metropolitan area and clipped the southwest corner of Mississippi before dropping to tropical depression status by 12:00 UTC on June 8 while centered near the Louisiana-Mississippi border. The blocking high was then pushed eastward by advancing deep-layer trough over the Rocky Mountains, and Cristobal accelerated northward along the Mississippi Valley, passing over Arkansas, Missouri, Illinois, and Iowa. During this time, the broad nature of the cyclone caused its pressure to drop and it bottomed out at 988 millibars (29.2 inHg) at 18:00 UTC on June 9. Six hours later, Cristobal became extratropical at 00:00 UTC on June 10, while situated over northeastern Iowa, the farthest northwest a fully-tropical system had traveled over North America in recorded history.[19] The storm was only the fourth tropical cyclone remnant on record to have moved over Wisconsin,[20] and the first since Gilbert in 1988. Green Bay, Wisconsin recorded an all-time low pressure observation for June when Cristobal caused readings to fall to 986 millibars (29.1 inHg), breaking a record set in 1917.[16]

Cristobal reached the Upper Peninsula of Michigan as a post-tropical cyclone by the early morning hours of June 10,[21][22] and the last public advisory issued by the Weather Prediction Center on Cristobal came later that morning, at 09:00 UTC. Multiple June low pressure records fell as Cristobal passed through the Marquette area.[23] A peak gust of 50 knots (93 km/h; 58 mph) was recorded at the Stannard Rock Lighthouse, just southeast of the Keweenaw Peninsula, as the storm moved across Lake Superior toward Northern Ontario, Canada.[23][24] In doing so, Cristobal became the first known case of a tropical system reaching Lake Superior.[23][25] At 12:00 UTC on June 10, Cristobal reached an extratropical peak of 982 millibars (29.0 inHg), as a tropical storm-force low, before weakening on the next day.[1] On June 11, Cristobal's remnant extratropical cyclone reached James Bay, in the southern portion of Hudson Bay, and slowed down, while making a southward turn, before dissipating on the next day, about 35 miles (56 km) south-southwest of Wemindji, Quebec.[1] Cristobal's remnant moisture was subsequently absorbed into another neighboring frontal system, which crossed over Labrador later that day.[26]

Preparations

Amanda

Guatemala and El Salvador

On the first advisory for Tropical Depression Two-E, the government of Guatemala issued a Tropical Storm warning for the entire coastline of Guatemala, from the Guatemala–Mexico border eastward to the El Salvador–Guatemala border. A tropical storm warning was also issued for the coast of El Salvador.[27] In Guatemala, nearly 1,500 shelters were opened for those affected by the storm.[28]

Cristobal

Mexico

In expectation of high winds and heavy downpours, a tropical storm warning spanning from Campeche westward to Veracruz was issued by the government of Mexico on June 1 as Tropical Depression Three was forecasted to strengthen in the Bay of Campeche.[29] A total of 9,000 Mexican soldiers and National Guard members were sent to assist with preparations and relief work.[30] Residents in several at-risk communities in the states of Tabasco, Campeche and Veracruz were evacuated on June 2. The Puerto Isla del Carmen terminal at the mouth of the Grijalva River was closed for vessels of all types as Cristobal approached; waves there reached up to 10 feet (3.0 meters) high on June 2.[31] On June 5, while Cristobal was downgraded to a tropical depression, a tropical storm watch was issued extending from Punta Herrero to Río Lagartos by the Mexican government.[32] This watch was upgraded to a warning six hours later.[1]

United States

With Cristobal tracking toward the state, Louisiana governor John Bel Edwards declared a state of emergency on June 4 and ordered evacuations for low-lying coastal areas.[33] On June 5, a tropical storm watch was issued from Intracoastal City, Louisiana, to the Alabama-Florida border. A storm surge watch was also issued for parts of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida.[34] The town of Grand Isle, Louisiana, issued a mandatory evacuation order starting on June 6 at 11:00 UTC, according to Grand Isle Mayor David Camardelle.[35] Later that day, Amtrak cancelled all trains throughout the area. U.S. President Donald Trump declared a federal state of emergency in Louisiana on June 7 as Cristobal approached landfall.[36] Additionally, flash flood and river flood watches were issued from Louisiana in the south to Wisconsin in the north due to rainfall estimates upward of 10–15 inches (250–380 mm) forecast in some areas, impacting more than 15 million people.[37]

Impacts

| Country/ Territory |

Deaths | Damage (2020 USD) |

Peak rainfall | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belize | 0 | — | 13.89 in (353 mm) | [4] |

| El Salvador | 30 | $200 million | 42.8 in (1,087 mm) | [4][38] |

| Guatemala | 5 | — | 26.48 in (673 mm) | [4] |

| Honduras | 5 | — | 13.73 in (349 mm) | [4] |

| Mexico | 3 | ≥$186 million | 34.1 in (865 mm) | [1][4][39][40][41][42] |

| United States | 3 | $310 million | 13.65 in (347 mm) | [1] |

| Totals: | 46 | $865 million | [3] |

Mexico and Central America

The combined effects of Tropical storms Amanda and Cristobal brought torrential rains to a large swath of Central America and Mexico. According to the National Hurricane Center, parts of the Pacific coasts of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Mexico's Chiapas state picked up 20 in (510 mm) of rainfall.[43]

Guatemala

On May 31, Amanda made landfall in Guatemala,[44] only the second tropical cyclone to make landfall on that nation's Pacific coast this century. The last storm to do so was Tropical Storm Agatha in 2010.[28] Amanda brought torrential rainfall to portions of Guatemala that produced flooding and landslides.[7] Two people died across the country.[45]

El Salvador

In El Salvador, torrential rainfall caused significant damage along coastal cities in the country as rivers overflowed and swept away buildings.[46] 25% of the country's annual rainfall totals fell in just 70 hours due to Amanda.[47] Rainfall reached 267.4 mm (10.53 in) in Izalco by the morning of May 31, prior to Amanda's landfall.[48] Amanda killed 30 people in El Salvador,[38] of which at least six died due to flash flooding, and one died from a collapsed home.[49] More than 900 homes were damaged across the country and 1,200 families were evacuated to 51 shelters across La Libertad, San Salvador, Sonsonate, and San Vicente. In the capital, San Salvador, 50 houses were destroyed and 23 vehicles fell into a sinkhole.[50][51] El Salvador President Nayib Bukele declared a 15-day national state of emergency due to the storm.[49] Movement restrictions in place for the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic were temporarily lifted to allow people to purchase medicines, while hardware stores were allowed to open with limited capacity so people could purchase equipment for repairs.[50] Around 7,225 people lost their homes and had to be sent to 154 shelters around the country.[52] At least 2,800 hectares of crops were damaged or lost in the country.[53] Additionally, around 30,000 structures were damaged or likely destroyed by flooding and mudslides.[54] Amanda was considered the worst weather disaster to effect El Salvador in 22 years since Hurricane Mitch, in which Amanda caused rainfall accumulations of at least 600 mm (24 in) in many parts of the country and Mitch only caused at least 400 mm (16 in) in other areas in a longer period of time.[55] Around 336,000 Salvadorans were pushed into severe food insecurity in both rural and urban areas.[56]

ACT Alliance promised at least US$75,000 worth of food and other emergency supplies to be supplied to 1,450 households across the country.[57] Damage was estimated at US$200 million (1.75 billion colón).[58][59][60]

Honduras

Despite being located relatively far away from where Amanda made landfall, five people died in Honduras due to the storm, including a brother and sister whose car was swept away by a current in Tegucigalpa. Heavy flooding affected the Valle Department in the west of the country. Maximum precipitation from Amanda was reported in the extreme southwest of Honduras, near the El Salvador border, where 9-day rainfall totals from Amanda and Cristobal peaked between 500–600 millimetres (20–24 in).[4]

Mexico

The National Meteorological Service of Mexico reported that 26.3 in (667 mm) of rain fell in Ocotepec, Chiapas between May 30 and June 3.[61] Mérida, the capital of Yucatán, recorded 22.9 in (581.66 mm) in the same time frame.[30] The widespread rainfall led to some significant flooding across the Yucatán Peninsula.[30] Some areas of Yucatán received a year's-worth of rain in four days.[40] Cristobal also caused minor damage to a PEMEX oil platform in the Gulf of Mexico and to the terminal at Isla del Carmen (near where it made landfall).[62]

At least 619 people had to be evacuated, due to the threat of incoming landslides and flash flooding. Additionally, 16 individual landslides were reported across Campeche, Chiapas, and Yucatán.[63] Around 10,000 people were estimated to have been severely affected by flash flooding.[64] Agricultural damage in Campeche reached 40 million pesos (US$1.84 million).[41] One person drowned while trying to swim through 6.2 ft (1.9 m) floodwaters in Santa María, Yaxcabá.[65] Another person died in Chiapas when a tree fell on him.[66]

In Yucatán, 95,000 hectares (230,000 acres) of crops were damaged, which is about 85% of the total crops statewide. The costs were calculated at 4 billion pesos (US$184 million).[40] Further east, in Lázaro Cárdenas, Quintana Roo, the heavy rain from Cristobal caused flooding and damaged 10 hectares (25 acres) of papaya. Total losses were estimated at 1 million pesos (US$46,000).[42]

United States

Ahead of the storm's landfall, two children died in Louisiana after being pulled to sea by a rip current,[67] and a third drowned in Texas due to the rough surf.[68] A 5 ft (1.5 m) storm surge caused flooding along much of the Louisiana coast, and flooded the only road leading to and out of Grand Isle, which was under a mandatory evacuation.[18] Torrential rainfall and the storm surge caused a flood event in Grand Isle said to have been the worst since Hurricane Isaac in 2012.[69] A large portion of Louisiana Highway 1 was completely flooded and inaccessible throughout June 7, and around 4,000 power outages occurred across New Orleans on that same day.[69] Infrastructural damage to southern Louisiana incurred a damage estimate near US$150 million.[70]

In Florida, several tornado warnings were issued and at least six tornadoes were confirmed in the state between June 6 and 7 from Cristobal's outer rainbands.[67][71] A destructive EF1 tornado struck areas just east of Downtown Orlando, starting as a waterspout over Lake Conway before moving ashore and damaging or uprooting multiple trees, some of which fell onto homes.[72][73] The tornado caused about $956,000 of property damage.[1] However, the heavy rainfall from Cristobal relieved a seasonal drought in the state, where some parts of North Florida recorded over 10 inches (250 mm) of rain in just a day.[74]

In Mississippi near where Cristobal made landfall, several weather observation sites reported strong tropical storm-force winds.[75] A Weatherflow site on Ship Island, Mississippi, observed a sustained wind of 48 mph (77 km/h) and a gust to 64 mph (103 km/h), which was the peak wind gust reported during landfall in the United States.[76] Flooding became severe over Mississippi following Cristobal's landfall, and a state of emergency was declared by Mississippi governor Tate Reeves on June 10 to help speed up relief efforts; preliminary damage estimates in the state reached US$5.2 million.[77]

Downgraded to a tropical depression, Cristobal merged with another storm system coming from the west, bringing torrential rainfall and gusty winds across the Midwestern states.[78][79][80] The system brought stormy weather to the Great Lakes Region, accompanied by strong winds and high waves along the north end of Green Bay, especially across Big Bay de Noc in Michigan's Upper Peninsula.[25] Data retrieved at 06:00 UTC on June 10 from the GPM satellite found the heaviest rainfall occurring in two areas: north and west of Lake Superior, north of Rossport and Red Rock, Ontario, Canada; and over Georgian Bay on the eastern side of Lake Huron. In both places, rain was falling at rates of 1 inch (25 mm) per hour.[21] The storm became the wettest tropical storm on record in Minnesota.[81] Interstate 41 was closed for a brief time due to flooding from the storm.[82]

The large volume of moisture dragged behind Post-Tropical Cyclone Cristobal as it moved to the north prompted a rare moderate risk of severe thunderstorms to be issued for large portions of Michigan, Indiana and Ohio by the Storm Prediction Center in their categorical outlook.[83][84] A squall line associated with Cristobal's remnants, later classified as a derecho,[84][85] brought wind gusts up to 70 miles per hour (110 km/h) around the areas; 650,000 people lost power due to the derecho from Indiana and Michigan to western New York.[86][87] The derecho produced three EF0 tornadoes in Ohio as well as a high-end EF1 tornado in Beaver County, Pennsylvania on June 10, the later of which snapped dozens of trees and several power poles.[88][89]

Canada

The same thunderstorm line also impacted Southern Ontario and Western Quebec.[90] More than 43,000 households lost electrical power in Ontario.[91] In Quebec, the winds resulted in over 130,000 households losing power, about half of which were located in the Greater Montreal Area.[92]

Fierce winds and torrential rain accompanied by hail stormed through the District of Muskoka, causing extensive damage. Wind gusts of up to 100 kilometres per hour (62 mph) were reported at the airport in Bracebridge.[93] EF1 tornadoes also touched down near Bracebridge and Baysville, as did an EF2 tornado near Mary Lake.[90][94] Two additional tornadoes struck the London area: an EF0 tornado in Glencoe and an EF1 tornado in Belmont.[95][96]

See also

- Weather of 2020

- Tropical cyclones in 2020

- Other storms with the name Amanda

- Other storms with the name Cristobal

- List of derecho events

- Tornadoes of 2020

- Hurricane Isidore (2002) – A storm that took a similar track from the Yucatán to the Louisiana coast.

- Tropical Storm Alma (2008) – Also impacted El Salvador

- Tropical Storm Arthur (2008) – Was a regeneration of Tropical Storm Alma; also impacted the same areas in Central America

- Tropical Storm Agatha (2010) – Caused catastrophic flooding in Central America, particularly Guatemala

- Tropical Storm Hermine (2010) – Atlantic tropical storm that formed from the remnants of Eastern Pacific Tropical Depression Eleven-E

- Tropical Storm Selma (2017) – Also impacted El Salvador and Guatemala

- Hurricane Delta (2020) – Affected the Yucatán as well as Louisiana later in the season

- Tropical Storm Claudette (2021) – A storm that took a similar track and affected Louisiana around the same time a year later.

- Hurricane Grace (2021) – A storm which crossed over Mexico and had its remnants form Tropical Storm Marty (2021)

Notes

- ^ a b According to the NHC's protocol on cross-basin storms, any tropical cyclone that degenerates into a remnant low (or a remnant circulation) in one basin and later regenerates in another one is automatically given a new name and treated as two separate cyclones. Only storms that make the crossover as a tropical cyclone (tropical depression or stronger) will retain the same name.[1]

- ^ All values for sustained wind estimates are sustained over 1 minute, unless otherwise specified.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Berg, Robbie (January 13, 2021). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Cristobal (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ^ AFP (June 3, 2020). "Tropical Storm Amanda death toll rises to 26 in Central America". RTL. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ a b "Global Catastrophe Recap: August 2020" (PDF). AON Benfield. September 11, 2020. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 14, 2020. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Berg, Robbie (September 10, 2020). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Amanda (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- ^ NHC_TAFB (May 30, 2020). "May 30 10AM: A Central American Gyre over the eastern Pacific and northern Central America is producing large clusters of thunderstorms. These thunderstorms will continue to occur over Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, Belize, and southeastern Mexico thru next week (1/2)pic.twitter.com/biwz3Ka9fc". @NHC_TAFB. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ a b Gutro, Rob (June 1, 2020). "NASA Catches Short-Lived Tropical Storm Amanda". Greenbelt, Maryland: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ a b Aspegren, Elinor (June 2, 2020). "Tropical Storm Amanda weakens after killing 17 people in El Salvador and Guatemala, could reform next week in Gulf of Mexico". USA Today. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ Daniel Brown; John Brennan (May 31, 2020). "Two-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ Jack Beven (May 31, 2020). "Two-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ Stacy R. Stewart (June 1, 2020). "Two-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ Daniel Brown (June 1, 2020). "Two-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ Phillips, Patrick (June 1, 2020). "Tropical Depression #3 forms in Gulf of Mexico". Charleston, South Carolina: WCSC. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ Orr, Margaret (June 10, 2020). "What we learned from Tropical Storm Cristobal". New Orleans, Louisiana: WDSU. Archived from the original on June 21, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ Berger, Eric (June 2, 2020). "The Atlantic's third storm has formed in record time, and it's a threat". arstechnica.com. Archived from the original on June 17, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ a b c Henson, Bob (June 4, 2020). "Now a Depression, Cristobal Still Expected to Reach U.S. Gulf Coast as Tropical Storm". Weather Underground. Archived from the original on June 20, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c Puleo, Mark (June 10, 2020). "As Cristobal tapers off, here's what history will remember about the unique storm". AccuWeather. Archived from the original on June 16, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ Gray, Jennifer; Jones, Judson (June 3, 2020). "Cristobal makes landfall in Mexico and could loop back toward the US Gulf Coast this weekend". CNN. Archived from the original on June 16, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ a b Betz, Bradford (June 7, 2020). "Tropical Storm Cristobal makes landfall over Louisiana, packing strong winds and rain". Fox News. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "Cristobal – The First of its Kind in Wisconsin". weather.gov. Milwaukee/Sullivan, Wisconsin: NWS Forecast Office. June 12, 2020. Archived from the original on June 15, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ Noel, Katherine (June 9, 2020). "Former tropical storm Cristobal moves into southern WI". wkow.com. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ a b "NASA finds post-tropical depression Cristobal soaking the Great Lakes". Greenbelt, Maryland: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center. June 10, 2020. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved June 10, 2020 – via EurekAlert!.

- ^ Keith Jaszka (June 10, 2020). "Area Forecast Discussion". Cleveland Ohio: National Weather Service. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c Lafond, Kaye (June 18, 2020). "Cristobal the first tropical cyclone to track over Lake Superior". Traverse City Record-Eagle. Archived from the original on June 28, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ NNL Weather Update (June 10, 2020). "Cristobal Remnants Are Drenching the Region Today". Thunder Bay, Ontario: NetNewsLedger. Archived from the original on June 27, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ a b Haddad, Ken (June 10, 2020). "Tropical Depression Cristobal crosses over Lake Superior; 10-foot waves possible in Upper Peninsula". Detroit, Michigan: WDIV-TV / ClickOnDetroit. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ Day, Cindy (June 12, 2020). "Cristobal comes calling". The Telegram. St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Archived from the original on June 13, 2020. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ John Cangialosi; Andrew Latto (May 30, 2020). "Tropical Depression Two-E Advisory 1". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Kelley, Maura (June 2, 2020). "Amanda leaves destructive flooding in El Salvador, Guatemala". accuweather.com. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ Jack Beven (June 1, 2020). "Tropical Depression Three Discussion Number 2". Miami, Florida: NWS National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c Spamer, Courtney (June 7, 2020). "Cristobal unleashes life-threatening flooding in Mexico, Central America despite weakening". AccuWeather. Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Neftalí Ortiz (June 2, 2020). "Se Convierte Tormenta Tropical "Amanda" En "Cristóbal"; Efectos Provocan Anegaciones En Frontera" [Tropical storm "Amanda" turns into "Cristóbal"; effects cause flooding in the border]. Tabasco Hoy (in Spanish). Villahermosa, Tabasco, México. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ Jack Beven (June 5, 2020). "Tropical Depression Cristobal Tropical Cyclone Update". Miami, Florida: NWS National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ Golembo, Max; Deliso, Meredith (June 4, 2020). "State of emergency declared in Louisiana ahead of Tropical Storm Cristobal". New York City: ABC News. Archived from the original on June 16, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ Richard Pasch (June 5, 2020). "Tropical Depression Cristobal Advisory Number 16". Miami, Florida: NWS National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ Gray, Jennifer; Ward, Taylor (June 5, 2020). "Cristobal is now a tropical storm as it threatens the Gulf Coast". CNN. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ KATC News (June 7, 2020). "Emergency declared in Louisiana ahead of Cristobal". Lafayette, Louisiana: KATC. Archived from the original on June 16, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ Gray, Jennifer; Garrett, Monica (June 8, 2020). "Tropical Depression Cristobal moves inland, but the flooding threat is far from over". CNN. Archived from the original on June 16, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ a b "WFP El Salvador Situation Report #2 - Tropical Storm Amanda (17 June 2020)" (PDF). World Food Programme. June 22, 2020. Retrieved October 24, 2021 – via ReliefWeb.

- ^ Reporte Tormentas Tropicales Amanda y Cristóbal [Report: Tropical Storms Amanda and Cristóbal] (PDF) (Report) (in Spanish). Coordinación Nacional de Protección Civil. November 6, 2020. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c "85% de los cultivos de Yucatán se perdieron por Tormenta Tropical "Cristóbal": Mauricio Vila" [85% of Yucatán's crops were lost to Tropical Storm "Cristóbal": Mauricio Vila]. El Heraldo de México (in Spanish). Mexico City. June 8, 2020. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ a b "Más de mil en albergues; daños al agro por 40 mdp" [More than a thousand in shelters; damages to agriculture at 40 million pesos] (in Spanish). Tribuna Campeche. June 6, 2020. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- ^ a b Maya, Zona (June 9, 2020). "Pérdidas por 1 mdp dejó la tormenta 'Cristóbal' en cultivos de papaya en Lázaro Cárdenas" [Losses of 1 million pesos caused by the storm 'Cristóbal' in papaya crops in Lázaro Cárdenas] (in Spanish). Palco Noticias. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- ^ "Tropical Storm Cristobal a U.S. Gulf Coast Threat After Making Landfall Along Mexico's Bay of Campeche Coast". weather.com. June 3, 2020. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ Daniel Brown (May 31, 2020). "Tropical Storm Amanda Intermediate Advisory Number 3A". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ "Tormenta tropical "Amanda" deja 26 muertos en Centroamérica". Diario Las Américas (in Spanish). June 3, 2020. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ "La tormenta tropical Amanda provoca inundaciones y el desbordamiento de ríos en El Salvador" [Amanda, degraded to a tropical depression, causes flooding and overflowing rivers in El Salvador]. Noticias de El Salvador - elsalvador.com (in Spanish). May 31, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ "Appeals – IFRC". www.ifrc.org. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ Ministerio de Medio Ambiente [@MedioAmbienteSV] (May 31, 2020). "#ElObservatorioInforma 4:35 a.m. Lluvia máxima registrada en las zonas occidental, central, paracentral y oriental del país. PO" [#ElObservatorioInforma 4:35 a.m. Maximum rainfall recorded in the western, central, paracentral and eastern areas of the country. PO] (Tweet) (in Spanish). Retrieved May 31, 2020 – via Twitter.

- ^ a b "Alerta Roja por lluvias: Tormenta tropical Amanda deja al menos siete fallecidos y severas inundaciones en El Salvador" [Red alert for rains: Tropical storm Amanda leaves at least eleven dead and severe floods in El Salvador]. Noticias de El Salvador – La Prensa Gráfica | Informate con la verdad (in European Spanish). Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ a b "Hurricane Amanda kills 14 people in El Salvador". Seven News. June 1, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ "Deadly Tropical Storm Amanda hits El Salvador, Guatemala". Channel NewsAsia. Agence France-Presse. June 1, 2020. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ "ACT Rapid Response Fund: Emergency Response to Tropical Storm Amanda in El Salvador (RRF 05-2020) – El Salvador". ReliefWeb. June 23, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ "Impact Snapshot: Tropical Storm Amanda and Tropical Storm Cristobal As of 8 June 2020 – El Salvador". ReliefWeb. June 9, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ "Storm Amanda is the last straw for families in El Salvador amid COVID-19 | MSF". Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) International. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ "UNICEF El Salvador Humanitarian Situation Report No. 1 (Tropical Storm Amanda) - 31 May-10 June 2020.pdf" (PDF). ReliefWeb. June 4, 2020.

- ^ "Tropical Storm Amanda severely impacts food security of 340,000 Salvadorans | World Food Programme". www.wfp.org. June 8, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ "Tropical Storm Amanda El Salvador RRF 05-2020". Actalliance. June 22, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- ^ "Global Catastrophe Recap – May 2020" (PDF). AON Benfield. June 9, 2020. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ Lessner, Justin (June 3, 2020). "Tropical Storm Leaves At Least 20 Dead In El Salvador And Now Threatens The U.S. Gulf Coast". we are mitú. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ "Tropical Storm Amanda kills 14 in El Salvador". BBC News. June 1, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ National Hurricane Center [@NHC_Atlantic] (June 4, 2020). "Heavy rains and flooding continue over portions of southeastern Mexico and Central America from #Cristobal. The national meteorological service of Mexico (@conagua_mx) reports that 26.26 inches (667 mm) of rain has fallen at Ocotepec, Chiapas, over the past 5 days (May 30 – June 3)" (Tweet). Retrieved June 8, 2020 – via Twitter.

- ^ Voytenko, Mikhail (June 4, 2020). "Cyclone Cristobal damaged oil platform, floating dock, Gulf of Mexico". fleetmon.com. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "Tormenta tropical Cristóbal en México: daños, pronóstico y trayectoria de los próximos días" [Tropical storm Cristóbal in Mexico: damage, forecast and trajectory for the next few days] (in European Spanish). Infobae. June 4, 2020. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- ^ "Tormenta tropical "Cristóbal" deja 10 mil afectados en Yucatán ante contingencia por Covid-19" [Tropical storm "Cristóbal" leaves 10,000 affected in Yucatan due to Covid-19 contingency] (in Spanish). Mexico City: El Universal. June 6, 2020. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- ^ Ortiz, Graciela H.; Graniel, Gabriel (June 7, 2020). "Reportan dos muertos por afectaciones de "Cristóbal" en sureste" [Reports of two deaths due to effects of "Cristóbal" in the southeast]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "Tormenta tropical "Cristóbal" deja un muerto en Chiapas" [Tropical storm "Cristóbal" leaves one dead in Chiapas] (in Spanish). Mexico City: El Universal. June 4, 2020. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ^ a b Fedschun, Travis (June 7, 2020). "Tropical Storm Cristobal spawns damaging tornado in Orlando; Louisiana brothers, 8 and 10, killed in rip current". Fox News. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "Teen drowns at Crystal Beach after grandmother lost sight of him". Houston, Texas: KTRK-TV. June 8, 2020. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ a b Hunter, Michelle (June 7, 2020). "'Highest water' since Isaac: Tropical Storm Cristobal tidal surge flood Grand Isle roads". NOLA.com. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Ling, Danielle (June 10, 2020). "KCC issues insured loss estimate from Tropical Storm Cristobal". propertycasualty360.com. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ "Storm Prediction Center Storm Reports for 06/06/2020: Tornado Reports". www.spc.noaa.gov. Storm Prediction Center. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- ^ "National Weather Service Raw Text Product, Displaying AFOS PIL: PNSMLB". Melbourne Florida: National Weather Service. June 7, 2020. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 7, 2020 – via The Iowa Environmental Mesone, Iowa State University.

- ^ Brieskorn, Katlyn (June 6, 2020). "EF-1 tornado caused more than $870K in property damage, officials say". Orlando, Florida: WFTV. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- ^ Erdman, Jonathan (June 11, 2020). "Tropical Storm Cristobal Almost Wiped Out Gulf Coast Drought". The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ Tropical Storm Cristobal Sets Records on YouTube. Weathernation. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ Daniel Brown; Andrew Latto (June 7, 2020). "Tropical Storm Cristobal Update". Miami Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- ^ WLOX Staff (June 6, 2020). "State of emergency declared following Tropical Storm Cristobal, extensive damage evident across Miss. Coast". Biloxi, Mississippi: WLOX. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- ^ Rice, Doyle (June 9, 2020). "Remnants of Cristobal to merge with another storm, wallop upper Midwest with rain, wind". USA Today. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- ^ "Minnesota Weather: Unconfirmed Tornado Spotted In Renville; Heavy Rains, Flash Flooding In SE Minn". Minneapolis, Minnesota: WCCO. June 9, 2020. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ Rosenberg-Douglas, Katherine (June 9, 2020). "Cristobal's remnants bring strong winds to Chicago area as tornado warning, severe thunderstorm watch in effect". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- ^ Maximum Rainfall caused by North Atlantic and Northeast Pacific tropical cyclones per state (1900-2020), NHC

- ^ "Flooded Interstate 41 in Fond du Lac reopens after more than 5 hours closed". FDL Reporter. June 10, 2020. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Cappucci, Matthew (June 10, 2020). "Cristobal's final act: Severe storms likely over Great Lakes and Northeast as system sweeps into Canada". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ a b Cappucci, Matthew (June 11, 2020). "Midwest derecho knocks out power to 650,000, brings winds to 80 mph". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 22, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ Erdman, Jonathan (June 12, 2020) [First published June 10, 2020]. "A Derecho, a Widespread Destructive Thunderstorm Wind Event, Swept Across Michigan, Indiana, Ohio, Wednesday". weather.com. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ Dale, Emma. "Severe storms could bring 70 mph winds, tornadoes to metro Detroit". freep.com. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ Lada, Brian. "650,000 in the dark after severe storms leave trail of damage across Midwest". accuweather.com. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ Ricciutti, Gerry (June 11, 2020). "National Weather Service confirms tornado touched down in Columbiana County". wkbn.com. Youngstown, Ohio: WKBN-TV. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ "July 10, 2020 tornadoes". NCDC. National Weather Service. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ a b Robinson, Mark (June 18, 2020). "What it's like to chase the storms that spawned five tornadoes in Ontario". The Weather Network. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ Agence QMI (June 11, 2020). "Violents orages sur une partie de l'Ontario" [Severe thunderstorms over part of Ontario]. Le Journal de Montréal (in French). Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ Ferah, Mayssa (June 11, 2020). "Nombreuses pannes de courant à travers le Québec" [Numerous power outages across Quebec]. La Presse (in French). Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ Arsalides, Mike (June 11, 2020). "Storm leaves path of destruction through Bracebridge". CTV News. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ Crosse, Doug (June 19, 2020). "3 twisters hit Muskoka on June 10, says Northern Tornadoes Project". muskokaregion.com. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ Bicknell, Bryan (June 11, 2020). "Tornado damage in southwestern Ontario could have been much worse". CTV News. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ ICI Toronto (June 11, 2020). "Deux possibles tornades dans le Sud de l'Ontario" [Two possible tornadoes in southern Ontario]. Radio-Canada (in French). Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

External links

- The NHC's advisory archive on Tropical Storm Amanda (2020)

- The NHC's advisory archive on Tropical Storm Cristobal (2020)

- Tropical Storm Cristobal Floods Mexico & Central America – Jun. 2 / Jun. 5, 2020 on YouTube, Disaster Compilations.

- Tropical Storm Cristobal Hits Louisiana, Mississippi, & Alabama – Jun. 7, 2020 on YouTube, Disaster Compilations.

Tropical cyclones of the 2020 Pacific hurricane season | ||

|---|---|---|

Tropical cyclones of the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season | ||

|---|---|---|

DONATE

DONATE![[Map of 1950-2017 CONUS Hurricane Strikes]](http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/climo/images/conus_strikes_sm.jpg)